- Home

- Zucchino, David

Wilmington's Lie

Wilmington's Lie Read online

ALSO BY DAVID ZUCCHINO

Myth of the Welfare Queen

Thunder Run

WILMINGTON’S

LIE

THE MURDEROUS COUP OF 1898 AND THE RISE OF WHITE SUPREMACY

DAVID ZUCCHINO

Copyright © 2020 by David Zucchino

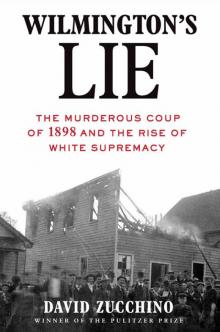

Cover design by Bárbara Abbês

Cover photograph: Armed rioters pose with the destroyed

Record building, Wilmington, North Carolina, 1898.

Courtesy of New Hanover County Public Library,

North Carolina Room

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or [email protected].

Photo credits are as follows: Photos 1.1 (fugitive slaves), 2.1 (Alfred Moore Waddell), 7.1 (rapid-fire gun crew), 7.2 (state militiamen), 12.2 (armed escort): Courtesy of the Cape Fear Museum of History and Science, Wilmington, NC. Photos 1.2 (Abraham Galloway), 5.2 (George Rountree), 9.2 (Donald MacRae), 10.2 (Fourth and Harnett): Courtesy of New Hanover County Public Library, North Carolina Room. Photos 2.2. (Alexander Manly), 3.1 (Furnifold Simmons), 3.2 (Democratic Hand Book), 4.1 (cartoon 1), 4.2 (cartoon 2), 4.3 (cartoon 3), 4.4 (cartoon 4), 5.1 (“Remember the 6”), 6.2 (John C. Dancy), 10.1 (committee response), 12.1 (Daniel Russell): Courtesy of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson Special Collections Library. Photo 4.5 (Josephus Daniels): Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Photo 6.1 (William Everett Henderson): Courtesy of Lisa Adams. Photos 8.1 (Charles Aycock), 8.2 (Red Shirts), 11.2 (burning Record ): Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina. Photo 9.1 (Roger Moore): Courtesy of the Internet Archive/NC Government and Heritage Library, originally published in Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present, ed. Samuel A’Court Ashe (Greensboro, N.C.: C.L. Van Noppen, 1905). Photo 11.1 (Alex and Frank Manly): Courtesy of East Carolina University, Joyner Library.

FIRST EDITION

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

This title is set in 13-pt. Centaur by Alpha Design & Composition of Pittsfield, NH.

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: January 2020

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-2838-6

eISBN 978-0-8021-4648-9

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

20 21 22 23 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the dead and banished, known and unknown

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by David Zucchino

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

PROLOGUE

BOOK ONE : DAYS OF HOPE

ONE : Cake and Wine

TWO : Good Will of the White People

THREE : Lying Out

FOUR : Marching to the Happy Land

FIVE : Ye Men of Unmixed Blood

SIX : The Avenger Cometh

SEVEN : Destiny of the Negro

EIGHT : A Yaller Dog

BOOK TWO : RECKONING

NINE : The Negro Problem

TEN : The Incubus

ELEVEN : I Say Lynch

TWELVE : A Vile Slander

THIRTEEN : An Excellent Race

FOURTEEN : A Dark Scheme

FIFTEEN : The Nation’s Mission

SIXTEEN : Degenerate Sons of the White Race

SEVENTEEN : The Great White Man’s Rally and Basket Picnic

EIGHTEEN : White-Capping

NINETEEN : Buckshot at Close Range

TWENTY : A Drunkard and a Gambler

TWENTY -ONE : Choke the Cape Fear with Carcasses

TWENTY -TWO : The Shepherds Will Have Nowhere to Flee

TWENTY -THREE : A Pitiful Condition

TWENTY -FOUR : Retribution in History

TWENTY -FIVE : The Forbearance of All White Men

BOOK THREE : LINE OF FIRE

TWENTY -SIX : What Have We Done?

TWENTY -SEVEN : Situation Serious

TWENTY -EIGHT : Strictly According to Law

TWENTY -NINE : Marching from Death

THIRTY : Not the Sort of Man We Want Here

THIRTY -ONE : Justice Is Satisfied, Vengeance Is Cruel

THIRTY -TWO : Persons Unknown

THIRTY -THREE : Better Get a Gun

THIRTY -FOUR : The Meanest Animals

THIRTY -FIVE : Old Scores

THIRTY -SIX : The Grandfather Clause

THIRTY -SEVEN : Leave It to the Whites

THIRTY -EIGHT : I Cannot Live in North Carolina and Be Treated Like a Man

EPILOGUE

Photo Insert

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Index

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Charles Aycock —His speeches incited whites to attack blacks. Conspired to deny blacks the vote. Elected governor in 1900.

Claude M. Bernard —Republican US Attorney in Raleigh, failed to indict white supremacists for murders and coup

Robert H. Bunting —White Republican, US Commissioner in Wilmington, married to black woman

Thomas Clawson —White supremacist city editor of Wilmington Messenger, sold used press to Alex Manly

John C. Dancy —Black customs collector at Wilmington port, counseled appeasement of white supremacists

Josephus Daniels —Editor of News and Observer, militant voice of white supremacy campaign

Mike Dowling —Brawling leader of a Red Shirt brigade in Wilmington

George Z. “Gizzard” French —White Chief Deputy Sheriff in Wilmington, Republican targeted by coup leaders

Abraham Galloway —Escaped slave, Union spy, state senator, early leader of black defiance in Wilmington

William E. Henderson —Leading black lawyer and political figure in Wilmington

Captain Thomas C. James —Commander of a Wilmington Light Infantry company

Edward Kinsley —Massachusetts abolitionist, urged Abraham Galloway to raise black Union regiments in North Carolina

Reverend J. Allen Kirk —Outspoken black minister in Wilmington, wrote “A Statement of Facts”

Captain Donald MacRae —Commander of a Wilmington Light Infantry unit, brother of Hugh MacRae

Hugh MacRae —Wealthy president of Wilmington Cotton Mills Co., leader of Secret Nine conspiracy

Alexander Manly —Editor of black-readership Daily Record, confronted white power structure in Wilmington

Carrie Sadgwar Manly —Wife of Alex Manly and vocalist for Fisk University Jubilee Singers

John Melton —White Fusionist police chief of Wilmington, targeted by coup leaders

Thomas C. Miller —Entrepreneur, wealthiest black man in Wilmington, loaned money to whites and blacks

Colonel Roger Moore —Former Confederate off

icer, commander of Ku Klux Klan and Red Shirts in Wilmington

George Rountree —White lawyer in Wilmington, leading organizer of coup

Daniel Russell —Republican governor of North Carolina, member of Wilmington plantation gentry

Colonel William L. Saunders —Former Confederate officer from Wilmington, commander of Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina

Armond Scott —Young, ambitious black lawyer in Wilmington

Furnifold Simmons —State Democratic Party chairman, political organizer of white supremacy campaign

James Sprunt —Wealthy white owner of Sprunt Cotton Compress

J. Allan Taylor —Member of Secret Nine conspiracy, brother of Walker Taylor

Lieutenant Colonel Walker Taylor —Commander of Wilmington Light Infantry, member of Group Six conspiracy

“Pitchfork” Ben Tillman —US senator from South Carolina, led white supremacist attacks on the state’s blacks

Colonel Alfred Moore Waddell —Former Confederate officer in Wilmington, leading orator of white supremacy campaign

George Henry White —US congressman from North Carolina, only black man in Congress in 1890s

Silas P. Wright —White Republican mayor of Wilmington, targeted by coup leaders

The white man’s happiness cannot be purchased by the black man’s misery.

—Frederick Douglass

PROLOGUE

White Man’s Country

Wilmington, North Carolina, November 10, 1898

T HE KILLERS came by streetcar. Their boots struck the packed clay earth like muffled drumbeats as they bounded from the cars and began to patrol the wide dirt roads. The men scanned the sidewalks and alleyways for targets. They wore red calico shirts or short red jackets over white butterfly collars. They were workingmen, with callused hands and sunburned faces beneath their wide-brimmed hats. Many of them had tucked their trousers into their boot tops and tied cartridge belts around their waists. A few wore neckties. Each one carried a gun.

Throughout that summer and autumn, white men had been buying shotguns, six-shot pistols, and repeating rifles at hardware stores in the port city of Wilmington, North Carolina, set in the low Cape Fear country along the state’s jagged coast. It was 1898, a tumultuous midterm election year. White planters and business leaders had vowed to remove the city’s multiracial government and black public officials by the ballot or the bullet—or both. Few white men intended to navigate election week that November without a firearm within easy reach. There was concern among whites in Wilmington, where they were outnumbered by blacks, that stores would run dry on guns and that suppliers in the rest of the state and in nearby South Carolina would be unable to meet the demand.

Gun sales soared. J. W. Murchison, who operated a hardware store in downtown Wilmington, sold 125 rifles in October and early November alone. That was four or five times his normal sales. These were Colt and Winchester repeating rifles, capable of firing up to sixteen rounds in rapid succession. Murchison also sold more than two hundred pistols during that same period and nearly fifty shotguns. Owen F. Love, a smaller hardware dealer, sold fifty-nine guns of all types during October and early November. Murchison and Love were proper white men, which meant they sold firearms only to other white men and primarily to those who were supporters of the white supremacist Democratic Party. They did not sell to blacks. When pressed on the subject later, Owen Love responded, “I had no objection to selling to any respectable man, white or colored, but I would refuse to sell cartridges, pistols or guns to any disreputable Negro.”

Years later, one of the city’s leading white supremacists wrote, “It is doubtful if there ever was a community in the United States that had as many lethal weapons per capita as in Wilmington at that time.” This was only a slight exaggeration. Among the city’s whites, there were almost as many guns as men, women, and children. Wilmington, with a population of twenty thousand, was the largest city in North Carolina, but the demand for weapons had exhausted the supplies of all the gun merchants in town. They telegraphed emergency orders to dealers in Richmond and Baltimore, who loaded guns and bullets onto railroad cars headed south.

For months, whites had been railing against what they called “Negro rule,” though black men held only a small fraction of elected and appointed positions in the city and the state. White politicians and newspapers warned that if blacks continued to vote and hold office, black men would feel empowered to seize white jobs, dominate the courts, and rape white women. “Nigger lawyers are sassing white men in courts; nigger root doctors are crowding white physicians out of business,” complained Colonel Alfred Moore Waddell, a former Confederate officer who led the white gunmen as they raced through the streets on the morning of November 10.

In 1898, a field representative for the American Baptist Publication Society called Wilmington “the freest town for a negro in the country.” Three of the city’s ten aldermen were black, as were ten of twenty-six city policemen. There were black health inspectors, a black superintendent of streets, and far too many—for white sensitivities—black postmasters and magistrates. White men could be arrested by black policemen and, in some cases, were even obliged to appear before a black magistrate in court. Black merchants sold goods from stalls at the city’s public market—a rarity for a Southern town at the time. Black men delivered mail to homes at times of day when white women were unattended. They sorted mail beside white female clerks.

A black barber served as county coroner. The county jailer was black, and the fact that he carried keys to the lockup infuriated whites. The county treasurer was a black man who distributed pay to county employees, forcing whites to accept money from black hands. In 1891, President Benjamin Harrison had appointed a black man, John C. Dancy, as federal customs collector for the port of Wilmington. Dancy had replaced a white supremacist Democrat, and he drew an astonishing federal salary—$4,000 a year, or $1,000 more than the governor earned. A white newspaper editor ridiculed Dancy as “Sambo of the Custom House.”

Black businessmen pooled their money to form two small banks that loaned cash to blacks starting small businesses. Several black professionals ran small law firms and doctors’ offices, serving clients and patients of their own race. A black alderman from Raleigh, the capital, noted with some surprise that certain black men in Wilmington had built finely appointed homes with lace curtains, plush carpets, pianos, and even, he claimed, servants. The city’s thriving population of black professionals contradicted the white portrayal of Wilmington’s blacks as poor, ignorant, and illiterate. In fact, Wilmington’s blacks had higher literacy rates than virtually any other blacks in North Carolina, a state in which nearly a quarter of whites were illiterate.

For whites, this was an intolerable situation. The planters, lawyers, and merchants who had dominated Wilmington since its founding in 1739 had lost control of the city during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Through terror and intimidation by the night riders of the Ku Klux Klan, white supremacists had returned to power in the 1870s. They did not intend to surrender Wilmington again.

The armed men emerging from streetcars on the mild, sunny morning of November 10, 1898, had heard rumors that black men, in response to white gunmen coursing through the streets, were massing at the corner of North Fourth and Harnett Streets. The intersection lay at the heart of a predominantly black neighborhood known as Brooklyn. The white men were inflamed with excitement and eager to fire their weapons. Some had already shot rifles from a streetcar, sending rounds whistling past black homes and small businesses along nearby Castle Street. One of the men carried a .44-caliber US Navy–issue rifle, though he was not a member of the city’s Naval Reserves. Others wielded army or police revolvers, belt revolvers, or small pocket revolvers. A few of the younger men still owned guns their fathers or uncles had fired during the Civil War. Some veterans called the weapons blueless guns because the dark blue finish had worn off to expose a dull gray color.

The men moved in columns with their weapons raised, i

n something approaching a military formation. They swept past clapboard houses and muddy yards in a mixed neighborhood of blacks and whites at the edge of Brooklyn. Wilmington was not yet a uniformly segregated city. In fact, some considered it the most integrated city in the South, with blacks and working-class whites living side by side in each of the city’s five wards. But this was still the South. Some Wilmington neighborhoods were largely black, such as the First Ward and most of Brooklyn; or almost purely white, such as the tidy blocks of tree-lined streets near the Cape Fear River.

Around eleven o’clock on November 10, a group of whites from the mob arrived to find a crowd of black men gathered at North Fourth and Harnett Streets, outside a popular drinking spot called Brunjes’ Saloon. Some of the men were known to whites as “Sprunt niggers.” They worked as stevedores, laborers, and machine operators at the Sprunt Cotton Compress on the Cape Fear riverfront. They loaded boulder-size bales of cotton onto merchant ships bound for Europe. The compress was the largest cotton export firm in the country, providing jobs to nearly eight hundred black men.

Some of the Sprunt workers had abandoned their posts at the compress after hearing rumors that a white mob was burning black homes in Brooklyn and plotting to butcher blacks at Sprunt’s. No homes had been burned, and no one had been killed. But the Sprunt workers were convinced that their lives—and the lives of their wives and children—were at risk. They made their way to Brunjes’ Saloon, where they could see packs of white gunmen descending on the clay streets of their neighborhood. The white men were cursing blacks. The black men bristled and cursed them back.

The white men hollered for the blacks to disperse, which only offended and aroused them. A city newspaper reported that the black men were “in a bad temper.” They stood their ground, anxiously eyeing the growing cluster of armed white men on the opposite corner. As the two sides exchanged more curses and taunts, one of the white men shouted out the mob’s purpose: they were “going gunning for niggers,” he said. The rising tensions pierced the tranquillity of a pleasant fall day, bright and cool, with a gentle river breeze.

Wilmington's Lie

Wilmington's Lie